Attack

|

The object of war is not to die for your country but to make the other bastard die for his. George Patton

Attacks must be committed since tori needs realistic energy to train against. One school of thought insists that attacks be so committed that uke over-extends, almost falling over of their own accord. Others say that uke should resist to their utmost and not over-extend at all. Not surprisingly, it is best for tori to practise at both extremes to get a feeling for the range of possibilities available. It is also good for uke to attack in varying degrees so as to learn how it feels to be off-balanced, or not. Certainly, to stick to just one method is not useful. A natural aim is to be realistic. |

|

(a) The living uke

Uke is alive and remains conscious throughout the technique so needs to act alive and be responsive. Uke should not play dead but provide tori with ceaseless responsive pressure. One method to develop this responsiveness is for uke to constantly try to stand up with gentle pressure. Accordingly, whenever a gap allowing them to do so appears, they stand up, and if tori spots it in time, they deal with it as necessary. This should not be a struggle, rather it is more a case of uke just letting tori know that a large gap exists. Contrasting this, it is not sensible for uke to fight against an arm-lock; someone who resists an arm-lock is transmitting the unspoken message, “Please break my arm!” Developing a responsive body is in agreement with developing good aiki.

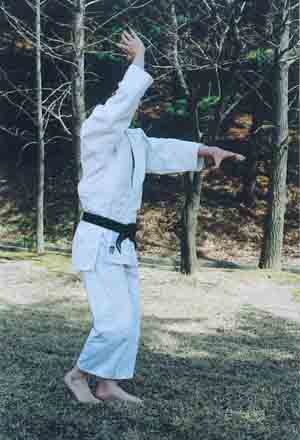

(b) Grabbing attacks The main striking attacks in Aikido are shomen-uchi, yokomen-uchi, and tsuki. Some schools also add gyaku yokomen-uchi, and uraken. Occasionally, there is an uppercut. In more modern terms, shomen-uchi reflects a simple down-blow, yokomen-uchi a roundhouse blow. One method to practice developing heavy striking power is to hit the mat hard when break-falling. Interestingly, in dealing with these striking attacks tori often responds in like manner, meeting shomen-uchi with shomen-uchi, and so on. Uke should make a solid, calculated dynamic attack. When raising the arm for a one-step shomen-uchi the body should move forward slightly as the arm raises but the rear foot must not yet pass the front. The rear foot only passes once the strike is on its way down, otherwise, the closing distance will leave a large inviting gap for tori to take advantage of with an easy jodan-tsuki or shomen-ate. It is also good practice for uke to hesitate, trying to confuse tori. Or, uke can walk around a little exhibiting different footwork before initiating the attack. For yokomen-uchi it is best to raise the striking arm up as in shomen-uchi, in front of the head - swinging it rearwards often results in too much telegraphing, and worse, one's own body might even follow it by winding back with the movement. For tsuki attacks, avoid the Karate style retracting fist; in Aikido it is best to keep both hands forwards to maintain balance, even when punching. Further, the Aikido punch is performed more like a thrust, often done vertically with the thumb uppermost, almost as if punching with a knife, using the upper two knuckles of the fist, and with the body weight behind it, rather than a boxing jab or karate twisting punch. Although slower, it will have a very forceful effect if striking home. Rare in the traditional styles is shomen-ate, an open palm strike upwards to the chin. Rather than being a hand strike, with the body behind it, it necessarily becomes a powerful push, and emerging from below it is difficult to see coming. Of course, it is up to each to vary their training according to taste. And though rare in Aikido, it certainly makes sense to develop a few strong, low kicks, albeit by oneself. Teachers should encourage this.

(d) Dealing with striking attacks Typically, against a shomen-uchi attack tori will make a shomen-uchi movement; against a yomkomen-uchi attack tori makes a yokomen-uchi movement. Making the same type of movement makes it easier for tori to learn to harmonise with uke. Once harmony is present after sustained practice, tori can, if desired, deal with a yokomen-uchi by using shomen-uchi movements, and vice-versa. After further practice, tori can begin to change the time, starting either earlier, or later, than the incoming attack. For example, if one imagines uke's raising and descending blow to comprise 360 degrees of movement, starting 180 degrees late tori can cut up strongly as uke cuts down, hitting their arm and deflecting it. Against a right handed yokomen-uchi attack, a left handed gyaku-yokomen-uchi movement helps deflect, and a right handed shomen-uchi to uke's arm ought knock it down, disable it, and allow one to get through to uke's rear. There are innumerable combinations that can be mixed together to make interesting practice.

(e) Faster than a flying fist Despite being a common sight in Aikido, catching a flying fist is almost impossible in reality. Aikido movement originates from the centre and as such, a moving body can not easily match the speed of the fist of a hand-art, from someone whose training initiates movement in the hand. In Judo one controls the body and moves out towards the arm - it is a body-art. In Aikido, one should control the mind of one's opponent first, and then their body - distracting their attention takes the mind, providing the opportunity to control the head, body, arm, hand, or whatever becomes available in the moment. In dealing with a tsuki attack it is not really practical to just catch it and move into say, ikkyo. Many of the standard tsuki kihon-waza need considerable modification to be of any real practical use. If the intention is to take hold of the arm, and that it must be if many Aikido techniques are to be performed, first try to distract by flicking fingers at eyes, or feigning a kick to the groin. In feigning an attack, tori is searching for a response from uke. If uke raises their arms up in protection, one might be able to take hold and perform ikkyo. If uke does not raise their arms up in self-protection, hit them again! Second, rather than grabbing the arm, it helps to hook it first with the lower fingers since grabbing it reduces one's owns options. With a loose grip, one is still somewhat free to change. Third, change your focus from uke's hand and place it on uke's elbow. The elbow moves lot slower than the hand and is easier to 'find' in the moment. It is also more useful to control the elbow than the hand. Fourth, keep in mind possible combinations - a switch to waki-gatame, or ude-garami may be possible. If it is ikkyo that is to be the result, then momentarily applying a waki-gatame style movement may disorient them enough to safely return to ikkyo. Another method is to temporarily forget ikkyo, move in for irimi-nage, and when throwing them down at the floor take the nearest arm for ikkyo, if it is ikkyo that must be done. The root of the problem of techniques like tsuki ikkyo is that people think the tsuki to be a jab, rather than a thrust with the body weight behind it. The jab is from a hand-first type art, the strong thrust more from a body-first type. The jab is faster and standard Aikido often cannot cope with it; to do so one needs to accept that fact and concentrate more on avoidance. To deal with a hand-art player, one needs to have enough skill to temporarily survive playing them at their game, then drawing them into one's own body-art environment where, hopefully, they lack skill.

(f) Initiating the attack Facing uke in posture is confrontational and could be said to be provoking attack. Offering the wrist is a lure, and it could be said that tori is inviting the attack. Feigning attack to create a response to use in one's technique is initiating an attack. Tori can also initiate the attack by just hitting uke, then deal with uke’s response. In fact, in certain schools tori initiates grabbing techniques with a shomen-uchi, which uke deflects down then moving to the side to take hold as in kata-dori or morote-dori. In initiating the attack, one has anticipated trouble and is acting accordingly. If one hits uke, then uke is hit; if uke responds, then aiki can develop. In a sense, initiating an attack is a kind of lure in Aikido that allows tori to take control of the time. If the object is to grasp uke's arm, then one could feign to uke in order to make them raise their arm to a position where it could be grabbed. A steal from Jujutsu is to create a hip throw in the moment. Rather than spotting a shape and taking advantage, tori lures or leads uke, creates the desired shape and takes advantage as it is being created. For example, if uke is in right posture, tori feigns a kick at uke's front knee with the instep of their right foot. As uke retreats their leg in avoidance, tori advances and moves forward in harmony stepping in with their right foot and entering for say, koshi-nage. If tori can move in at exactly the same time that uke retreats their leg then tori will be in position for the throw at the moment the shape for it is created. This is not about timing or fast reflexes, this is about control and harmony.

|

(g) Atemi

|

|

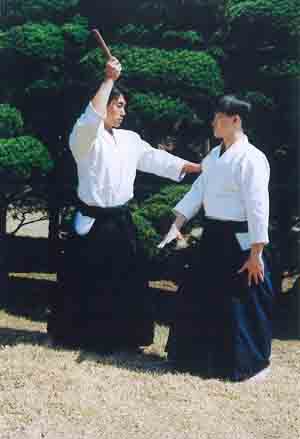

| Tori attacks. | Uke meets the attack. |

|

|

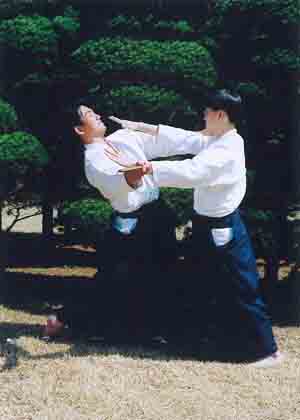

| Uke delivers first atemi to eyes with the left hand. | Uke delivers second atemi to eyes with the right hand. |

|

It is often heard said that Aikido is ninety percent atemi. While something of an enigma, if atemi is co-ordinated and well focused within aiki movement, then it certainly helps make the technique work. Note that atemi here usually refers to strikes performed by tori in the midst of technique. The key in delivering atemi is in not interrupting the flow of the technique thereby disturbing the aiki. Rather, it ought to contribute to the aiki flow. This is a very important point that is often completely ignored. While the most obvious form of atemi is a direct punch or kick to a vulnerable point, more dangerous forms of atemi are; jabbing at the eyes with one's fingers; stroking the back of one's hand across the eyes using the finger nails; hitting the side of the neck or throat with the inner or outer forearms; hitting uke's arms with the forearms; clapping a hand over the ear; using a back-fist to the lower ribs or hammer-fist to the kidneys; delivering an upper back-fist or kick to the groin; or head-butting uke when taking control as in sankyo or moving in close for koshi-nage. When close in, a knee to the groin or inner / outer thigh area will temporarily incapacitate uke. It is man's natural instinct to protect the groin, consider hitting or kicking the bladder instead; it is very effective and totally unexpected. An open hand is far more powerful than a fist for the average person, especially for those who do not train to punch. Indeed, boxers are commonly known to break their own fists in barroom brawls; their egos get the better of them. Or, use a fist for striking soft areas, an open palm-heel for the hard. Remember, it is important to aim every strike. In order to solve the enigma, to acquire the idea of what I believe to be real atemi in Aikido, one needs to practice constantly with the bokken. The shomen and yokomen striking movements can become principles in themselves that can be incorporated into one's techniques whether one uses them as strikes or not. In empty hand techniques, the up and down movements of shomen-uchi can be performed as parry, deflection, hit, or cut. Such can be delivered gently, or painfully. And even when moving into the midst of technique, those same principles used within the up and down movements can be applied again in redirecting uke to the mat. Finally, the idea of contact can also be thought of as atemi in the sense that, if uke makes contact with tori's centre, then that in itself constitutes an attack, which implies that if tori makes contact with uke's centre, tori is indeed, hitting uke. Thus, contact is subsequently maintained for the remaining ninety percent of the technique. Interestingly, if uke has good centre/contact, then even if tori parries his attack, the good uke should be able to instantly redirect it at tori's centre to 'win'.

(h) Half a hand It is traditionally implied that half-a-hand hits heavily enough to knock out; the full-hand kills. For more realistic training in Aikido it is useful to take this principle and tame it. For Aikido, I take half a hand to be a strike within the movement that may clonk the head, slap the face, touch the eyeball, or penetrate the body enough that it actually jolts uke, for real, not play, and that an onlooker would 'feel' it. From uke's point of view there is no lasting effect other than a slight toughening up over time. Contrasting this, the full-hand is hitting much harder, a real blow, enough to really incapacitate uke, making them almost fall into the technique. I should point out that this kind of full-hand does not mean hitting full force, as hard as one can hit. There is still control. From time to time, one needs to negotiate with uke and incorporate such half-hand strikes into the techniques to really appreciate the power of Aikido. Obviously, the full-hand is only for self-defence. To develop the half-hand, practise hitting uke in various places using different strikes such as a gentle punch, palm heel, back-fist, finger jab, shin kick etc. Such strikes should give uke a slight jolt, being either slow and heavy, or light and fast, but not too uncomfortable. To develop the full-hand, first hit the mat hard and heavy during ukemi, or just whack the forearm into the mat, then, direct it at uke and aim to hit with full force but, at the last moment, stop short. |

(i) Striking point

|

|

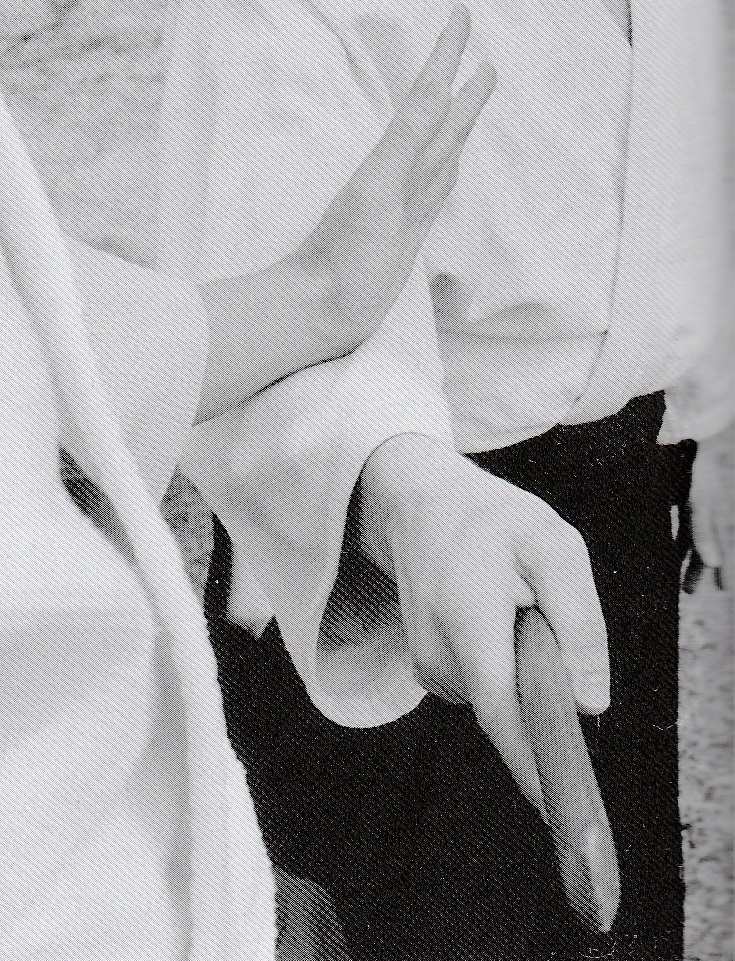

| One third up from the wrist. |

One third down from the elbow. |

|

|

|

One third down from the shoulder. |

|

|

When tori contacts uke's arm it should be in the form of an Aikido based movement such as yokomen-uchi or shomen-uchi. This movement can be light or heavy in feeling, and a parry, hit, or cut in form; when striking one must aim. For many Aikido techniques it is useful to aim to hit uke's arm heavily, approximately one third of the way down from the elbow, or sometimes, one third of the way down from the shoulder. Here, momentum is transferred to uke's arm with the prerequisite amount of pain. Any lower and the arm is likely dashed away. Another point to aim for is approximately one third the way up from uke's wrist. This lighter target needs a more jabby, lighter hit. When hitting heavily tori uses a point about one third of the way along their own forearm from the wrist, for lighter hits, closer to, or using, the tegatana is fine. Both of these types of hit can be done from inside or outside of uke's arms and this same feeling of striking can be used on other more vulnerable areas of uke's anatomy to great effect.

|

|

Some practical ideas - 1 Wrist Grabbing (Think - Process) Wrist grabbing gives tori the chance to learn bodily marital movement. How the wrist grab is dealt with also provides the key to movement in dealing with other attacks, such as being pushed or punched. The idea is to unify movement across a range of attacks and defences to simplify the process - to make it logical and therefore easy to learn. Tori likes his wrist to be grabbed because uke only has one more hand with which to attack; even if a wrist is grabbed, the smart tori still has two hands.

It is important to develop a tori-leading-uke feeling. When training,

it is important to practice at either end of the above continuum ranging from

light to solid, technical to realistic. With technical skill, tori can

allow uke to maintain a comfortable grip (more harmony), or, can chose to make

uke's grip feel uncomfortable (less harmony). It is unlikely that a

teacher will ask you to train systematically like this. Usually, the keen uke

attacks as strong he can; in his daily practise the keen tori varies his

own response according to the above methods - if he is aware of them. Some practical ideas - 2 Pushing (Think - Process)Pushing, here, can be done slowly or quickly and is along the way of logical progression to defence against striking. With a little thought, the skills learned here can be applied to striking. Also, what is learned here will improve body movement and general attack and defence skills. Below, 'touch' can represent a push or a strike.

Solid grips allow tori to refine his bodily movement such that it

harmonises with what uke is doing. Such practice is the absolute basic

requirement for kokyu-ho and kokyu-nage, which contain the basic

movements found in Aikido, which in turn must be applied in all the techniques.

Some practical ideas - 3 Striking (Think - Process) If you examine the methods of different arts it is not hard to come up with a few interesting ways to strike. Interestingly, there is more to a hit than just a hit. What you are thinking at the moment of impact can transform your strike to have varied effects. Some different types of strike follow:

Some practical ideas - 4 Dealing with attacks (Think - Process)After training against grabbing and pushing attacks, much of what has to be learned to deal with striking attacks is already known. Tori understands basic movement, avoidance, and has experience in dealing with uke's power. Striking attacks bring speed, power, and intention together to create danger.

Uke's attack provides tori with the opportunity to hone his skill. Tori can approach each technique in various ways that comprise some mix of the above ideas. There is no one way to do anything; rather, we have a bunch of variables that need to be trained. Some practical training ideas - 5 Real Attack (not for beginners)The first purpose of these attacks is for uke to defeat tori. The second purpose is to pressure tori to make better technique, if he can. If tori can't, don't let him. Just start again. These attacks are dynamic, a stage beyond the static. First, practise the attacks many times so that you get BETTER at them -- before trying the responses or escapes.

Tori will have to modify the way he begins ALL his techniques. The smart tori will figure out how by himself. If he can't, perhaps he is not yet ready to start with this method. Disclaimer: You might get hurt practising like this - GET USED TO IT ! |

Uke

remains aware and responsive throughout the technique.

Uke

remains aware and responsive throughout the technique.