Avoidance

|

There is no avoiding war, it can only be postponed to the advantage of others. Niccolo Machiavelli

Best to not be there. Best to not have let the situation deteriorate. And if there, best to lose a bit of pride than come to heated argument or violent exchange of blows. But one can not, and sometimes should not, avoid every unsavoury situation. At times one just has to argue one's point to illuminate ignorance, or fight for what one knows to be right. And when the fight is right, avoidance manifests itself in physical movement.

(a) Evasion |

|

|

To avoid an attack one needs to practice moving in eight directions. Forward and back, right and left, two corners to the front, and two to the rear. Many schools have a methodological routine for practising such, some do not. One needs to practice both by oneself, and with a partner. One can also avoid in an up and down direction, and by turning. Of course, one should practice turning, or taisabaki, along the eight directions too, both clockwise and anti-clockwise. The golden rule is not to look at the hands or feet while moving. Instead, look at nothing in particular, yet see everything. When moving, it is good to think in 3D. We have the X, Y and axes. Try to visualise the 8 directions shown to the left in each plane. A simpler way is to just think: up/down; left/right/ back and forth. Just as these ideas can be used to visualise avoidance, so they can be used to determine which way to move when doing a technique. |

|

Avoiding is not as simple as just moving out of the way. The following are different types of movement that use avoidance and could be, in the order they are shown, be incorporated into a learning process. Let's keep it simple: Imagine moving to the side to avoid a punch that is headed your way, say jodan-tsuki. Also, while doing it, notice how that as you push with the back foot that you also draw yourself forward with the front, which may or may not soon become a back foot as you move. 1 Avoid, just move out of the way (tori can still hit uke, but breaking his balance was not aimed for) 2 Avoid and touch, place you hands on the punch (it can have a leading-on / breaking balance effect sometimes) 3 Avoid and parry, push the punch slightly to the side (results in a smaller avoidance movement and allows you to move in) 4 Avoid, parry, and lead the attack on a little - try to lure uke forwards 5 Avoid and touch, and begin to push/redirect the arm (like say, ikkyo) - lure/lead uke forwards even more 6 Avoid and strike the arm 7 Avoid and grab the arm, and lead it on a little - more positive, it's like a gentle pull 8 Avoid, grab, and pull the arm (can off-balance, or if jerked can destabilize uke mentally) 9 Avoid slightly / parry slightly to redirect / and counter attack though the punch in the same time - my favourite Any shodan worth his salt will have done all of these many times and yet has probably never thought about them in any systematic way. The only way to improve is first to know what you are weak at and then to practice it. And if you teach, you need to know what to teach. All of the above exist (there may be more) but they are not incorporated into any Aikido learning system I know. |

|

| Move to the right and parry. | Move to the left and parry. |

|

|

|

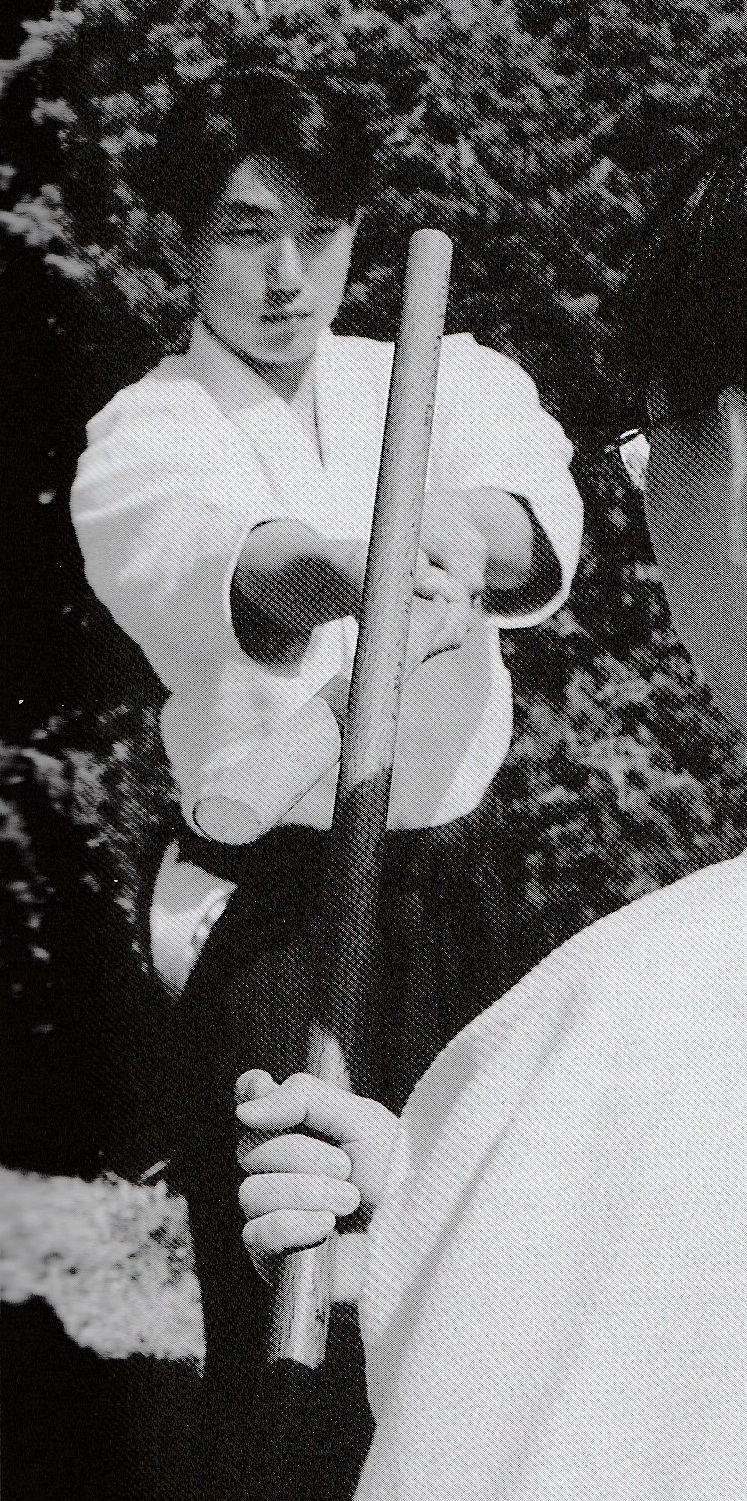

An excellent, perhaps indispensable, method of practising avoidance is training with the bokken and jo. Training with these tools one learns to move out of the way of one's partner's attack simply because it is so painful not to. But in so doing, one must take great care that the postures and movements made when using weapons are the same as those when performing Aikido, otherwise one will be learning separate arts, a common trait, unfortunately. As Aikido is a body art, it follows that one's movement in avoidance should originate from one's centre. One way to get a feeling for this is to clasp one's hands behind the back stretching out the chest and belly somewhat. Have uke punch fast, but not hard, and avoid it just enough so that it barley touches the chest or belly. It should feel as though uke's thrusting arm turns one's own body. Ninin-dori or tanin-dori training can be used to develop avoidance skills. Ukes simply rush tori, who moves out of the way and pushes them away. After a while, the push can be converted to kokyu-nage. This sort of practice is often seen in demonstrations where tori seemingly throws six or seven ukes repeatedly, often with the keen spectator casting a critical eye. This method is excellent for developing avoidance and co-ordination skills but it does not represent real skill in dealing with multiple attackers. Accordingly, this method of practice should be confined to the dojo. It is a means, not the end.

(b) Different approaches in principle In terms of being pushed at the shoulder from the front: 1 Just move out of the way to the side and avoid the push. 2 Step back with one or two steps rigidly, with no give in the body. Tori moves because uke shoves. Posture is maintained and the feeling is a little wooden. Training in this way may develop a correspondingly rigid attitude in the mind. There are benefits to this approach for some. 3 Step back with one or two steps, with give, somewhat floppily in the upper body to the left or right depending upon which was pushed. Tori's posture may be lost slightly if the push is strong, hence the rearward step. Uke may overbalance and tori can use this to begin technique. However, if tori becomes off-balance with this passive method the chance may be lost. 4 Step back quickly, in time with the push, the body feels floppy to uke but it is not. Tori retreats in harmony with uke's push. Uke feels as though their push peters out to nothing. Tori is in full control; uke may have lost balance. 5 Step back in time with the push, but, more than stepping back, say with the left, the feeling is of turning, and pressing the right side forwards, decisively, with intent. Here, tori is already upon uke and the emphasis is on forward counter attack. Of the above it cannot be said that one is better than the other. All exist, all are possible, all should be given consideration. Indeed, a person of weak disposition might benefit from training in the second method, toughening them up mentally somewhat. Further, allowing an aggressor to shove one will show all present clearly who is initiating the trouble, and receiving a couple of hard shoves might even satisfy the antagonist thereby dissolving the situation. |