Weapons

|

You can get more with a nice word and a gun than you can with a nice word. Al Capone

To learn to use weapons one needs to see many teachers, if only because many of them have little skill; daggers, swords and staves are no longer part of our culture - rare are those who truly know; modern Karateka busily practising their kama (sickle) kata would probably tire of cutting grass after ten minutes. |

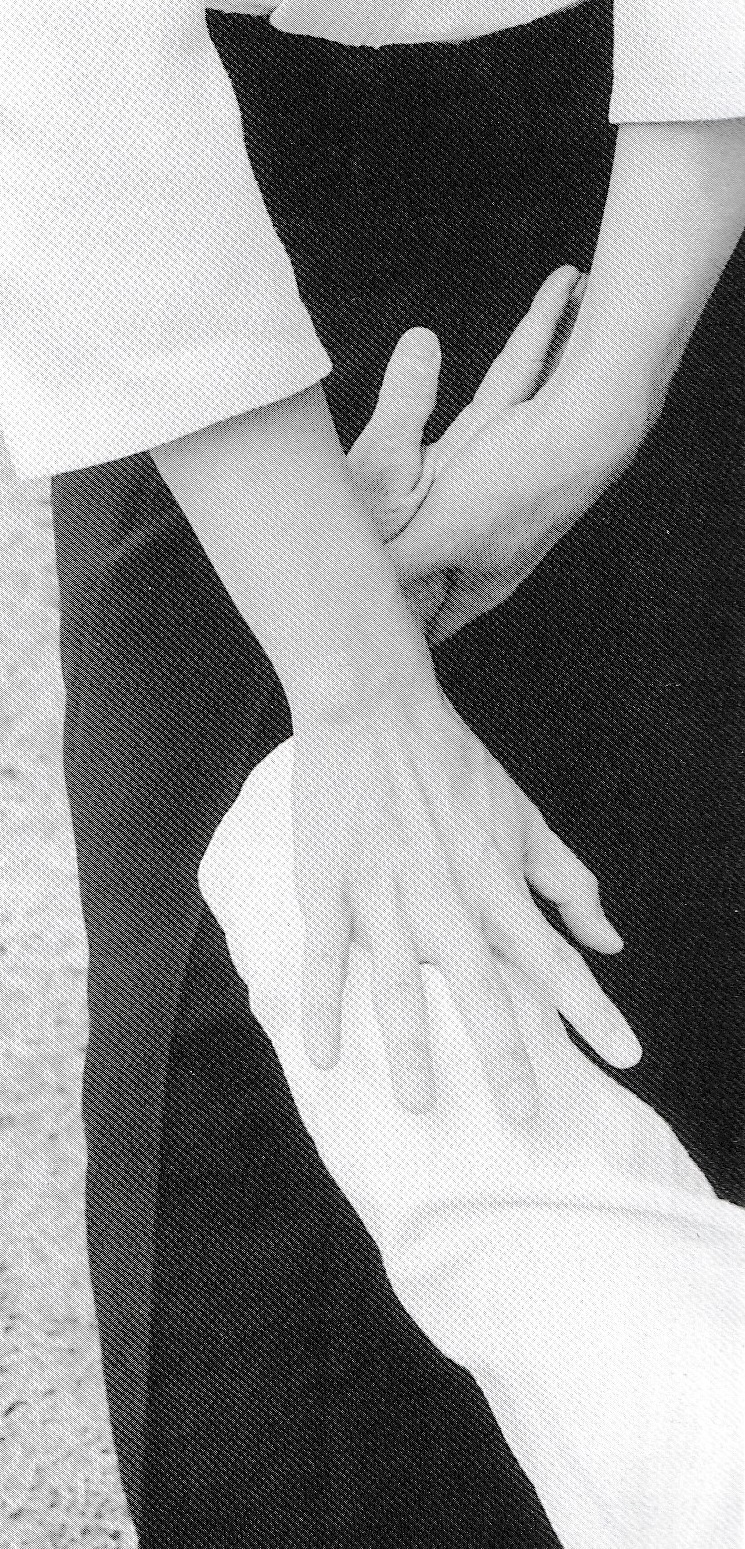

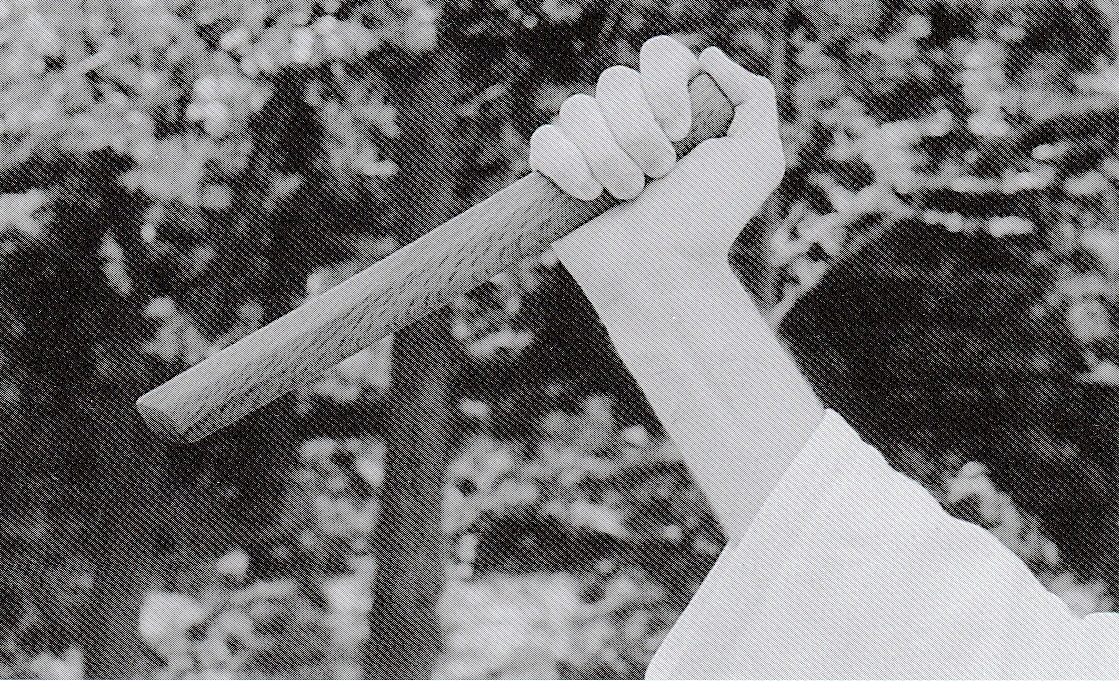

| Cutting up and down with uke’s arm creates Aikido techniques. | |

|

It is commonly believed that the point of weapons training in Aikido is to improve the empty hand techniques. With this in mind, since many of Aikido’s basic movements are based upon sword related principles, it certainly makes sense to practise using a sword, the enigma being, of course, that one could devote a lifetime of study to this weapon itself. |

|

(a) Bokken The usual method of holding a bokken is hands spread one fist-width apart to gain a measure of leverage when cutting. Rarely seen, but extant in Japanese arts, is to hold the bokken as one holds a baseball bat, hands close together. While swinging the bokken and cutting, the hands-spread method dictates that one punch slightly with the upper hand and pull with the lower at the point of striking. The feeling of cutting is also akin to the back pull of a saw. In fact, as a point of note, the Japanese saw cuts with the back-pull, unlike the Western the one that cuts with the push. So, the sword enters the opponent's body at the shoulder, cuts down, and then comes out – it is like a large slice; it is not a slash but a definite cut. With a fast cut, hitting with the end two to three inches of the blade the sword may snick in and out in a moment; in a heavy, slower, deeper cut, the body weight is added to the upper hand, to increase the power or depth of the cut, or rather, slice. When cutting with the sword in Aikido it is important to match the cut to one's body movement. For shomen-uchi the body moves forward or back when cutting. With yokomen-uchi it may seem that we move sideways as we cut. We should not. We turn, and when cutting, although the cut is diagonal to the temple or neck area, the body moves forwards or back, straight, just as in shomen-uchi. Some schools cut kesa, a large diagonal cut down the line of the keikogi, with the blade finishing near the tatami. Even in this case, if one is carried around by the momentum of the strike it is not correct. When cutting, think of torifune. Cut forwards. |

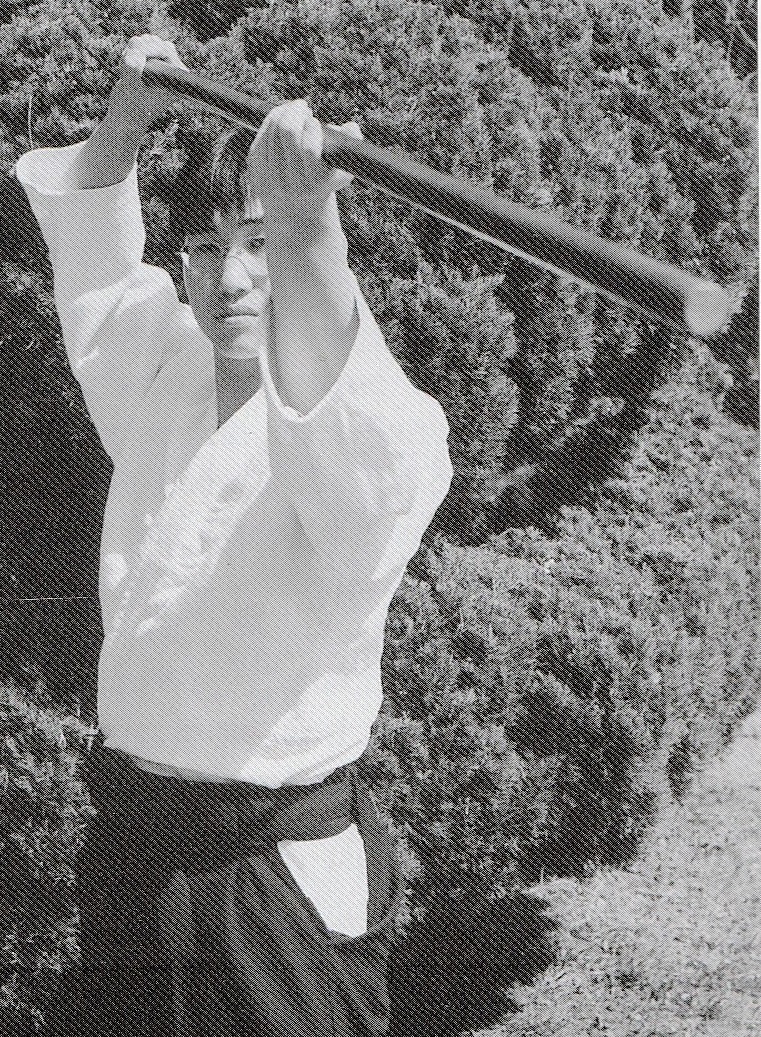

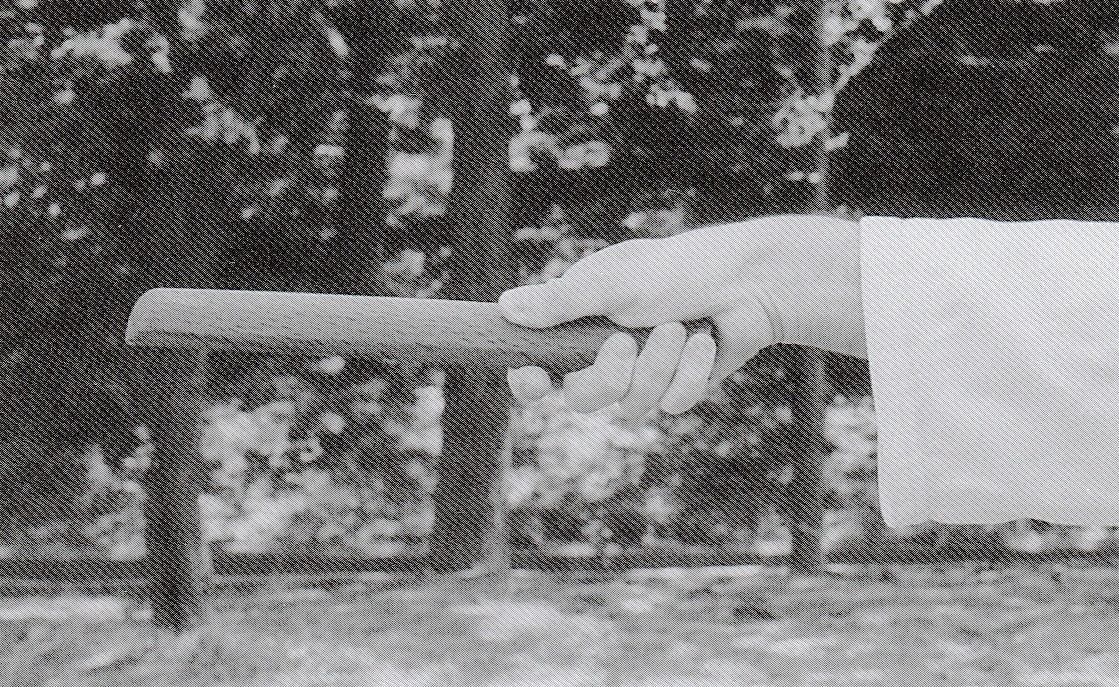

| Both tori and uke keep centre. | |

|

When practising with a weapon it is necessary to have a vivid imagination, a sense of what is really supposed to be happening. While it appears to be the norm to run through various kata or sequences of techniques, the real nitty-gritty of training is basic holding centre, evasion, cutting, and thrusting. And after each movement the tip of the weapon must return to point towards uke instantly lest the centre be lost. |

| One needs to practise against single cuts coming from a single direction and training various responses: Avoiding left or right, moving close enough to hit at the right time with an appropriate stroke; moving just out of range, but not so far that a counter is impossible; if one has barley avoided, there may be the need to parry; if one has avoided well, there is no need to parry at all, just strike; with no avoidance one must block, but being defensive, uke may gain the control of rhythm. Instead of the block is the counter strike, or forceful parry. This can be done with or without avoiding, and has the effect of dashing uke's sword back, as in irimi, or out, as in tenkan. Sometimes, a forceful parry can also turn into a counter strike in the same stroke, especially if the avoiding body movement has a forward component. Attacks are parried using the flat, or the back ridge. The blade edge could be used directly against a wooden weapon with the intention of cutting it, but not against a sword. When using the flat one has to push, not hit, otherwise one's own sword could be broken. Better is to use the back ridge by forcefully twisting one's sword against uke's. Done sharply, this has the effect of dashing uke's sword away while protecting the edge. One should also experiment transferring these movements to the jo and of course, the empty hand techniques. |

(b) Jo

|

|

|

Focus on uke |

Being focused upon |

| To maximise the thrust distance the jo is held with the little finger feeling the end, the other hand about a third of the way along. When performing Aikido type techniques on uke it is sometimes held with a few inches protruding from the lower hand - useful for hooking an arm, wrist, or neck. Other times it is held and used like a bokken, striking the opponent with the tip. As with the bokken above, it makes sense to practice avoiding, moving, and responding in all possible directions. Obviously different, the jo has two ends and is not sharp, but all of the same principles apply. It goes without saying that when training one should always try to hit and receive ever faster and harder. The imperative necessity to avoid adds a measure of reality to both maintaining mental composure and good technique under violent duress. For training a sharp counter strike, especially one with minimal or no avoidance, it is better to start with the jo than the bokken. Using the jo, the hands are typically held further apart than the bokken, which adds a measure of control that helps to both learn the principle while maintaining a degree of safety. Practice should be carried out on both left and right sides for dexterity – such is more likely to be done with the jo than the bokken in most dojos. |

(c) Tanto

| Standard downblow | Standard thrust |

|

|

|

There are four ways to hold the single bladed tanto. In a straight forward thrust, the blade can point upwards or downwards. For the downward stab, the blade likewise has two positions. For standard thrusting in Aikido the blade should be pointed upwards. While the tanto is only made of wood, one should imagine that the thrust has a degree of upwards motion that cuts upwards through the fleshy parts just below the ribs and up towards the heart. It is not so much a stab as an upwards singular, saw-like cut. In the downward blow the blade should be facing oneself with the thumb over the end to prevent slippage – Japanese tanto’s usually have no tsuba (blade guard). Thus when striking it not only stabs, but cuts as it enters, and once entered deeply, rather than withdraw it the way it went in, one could draw it back towards oneself while cutting upward slightly thereby causing more damage. Not nice, but that's the way it is practised in Aikido. The tanto blade could be reversed but then your thrusting technique would have to be modified accordingly. For example, in the forward thrust, you would have to cut downwards slightly, not up. Perhaps the weapon most need to relate to in modern times, one naturally needs to practise all Aikido techniques against tanto attacks from all possible directions. The direction of the strike often determines the pattern of avoidance and the nature of the technique so is easy for a smart tori to predict. The problem is that the tanto is a hand movement based weapon, not a body one. Typically, an Aikidoka attacks in the standard way putting their body weight behind the movement so there is no problem - except that it is less realistic. To broaden their scope, tori needs to practice moving in at least a couple of different directions for each type of strike. However, it is obvious that such will not work against a tanto used as a hand movement based weapon since the hand moves much faster than the body. Since Aikido technique depends on body movement, to deal with a fast tanto one has to learn to use the hands to deflect and/or take an arm before a solid Aikido technique can be applied. Here, an understanding of timing and the willingness to take a cut are crucial to success. Many Aikido techniques are performed against tanto attack. In each case, the distance and technique vary slightly. Some techniques on the syllabus are not sensible thus the keen student needs a discerning eye. For practical self-defence it makes good sense to develop a private collection of effective techniques based on simplicity and effectiveness. Tori can also take the tanto and apply aiki techniques with it in either hand. When training with uke one typically takes the weapon and leaves it on the floor at a distance such that they have to get up and take at least a step to retrieve it. Or, one takes it away and hands it back. Note that the polite way to hand over a tanto (or bokken) is with the blade towards oneself and the handle away from one's own strong hand, showing trust. |

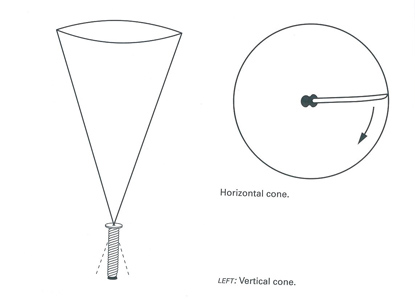

(d) Vertical or horizontal spirals

|

Holding a bokken or Jo vertically and drawing a circle above the head with the point creates a cone. The same can be done holding the sword out horizontally. Combining this movement with forward, or sometimes rear or sideways body movement creates a spiral. Spiral movements are very powerful and can be used for defence or attack with bokken and jo alike. When doing this, one’s centre should always move in unison with the bottom (handle) of the weapon.

|

|

(e) Mixing it up Empty hand against sword is fun but unrealistic in the sense that first, it is probably never going to happen in our modern society, and second, one would likely be cut down instantly against a real swordsman. Against a staff is more plausible. Against a knife could be the reality waiting around the next corner. Bokken against jo is also fun, and again, while it is almost never going to happen outside the dojo, it is useful to practice with weapons of differing lengths. The key to overcoming any weapon is to first know its strengths and weaknesses by using it. Therefore the key to any form of mixed practice is always in the basics; if one's basics are good, one may just have a chance when that sword-wielding lunatic jumps out in front of you. Finally, it is obvious that the stronger one strikes and receives in bokken or jo training, the better the practice. With weapons one can negotiate the terms with uke and really batter each other quite hard with safety. Accordingly. the occasional broken weapon in training can be considered as good practice. However, when training empty hand against jo, or performing kokyu-nage using the jo, a breakage is indicative of bad technique.

(f) Footwork Many schools practice bokken and jo kata yet fail completely to make any connections between the individual techniques found within that could lead a keen student to a more complete understanding of the weapon at hand. When facing uke, one can theoretically cut in any number of directions around a clock face and thrust jodan, chudan, or gedan along a left, right, or central plane. In reality, after avoiding a certain strike in a certain direction at a certain time, commonly, only one defensive option and counter strike will be available, at most, maybe two. Less choice means less hesitation but also makes it easier for a wise opponent to know what's coming. The most important point in learning is to build a framework of patterns of movement that are easy to visualise for the self and easy to recognise in an opponent. The easiest way to remember all the different attacking strokes is to cut around an imaginary clock. Twelve O’clock represents shomen-uchi. Eleven and One represent Yokomen-uchi or kesa. Nine and Three represent do, the midsection. Seven and Five represent upward rising cuts. Six is a vertical upward cut. These same attacking movements and directions can also be turned to the defensive. Putting bodyweight behind the blow and transferring the energy into the opponent’s weapon can have a blocking, parrying, or intercepting counter-strike effect. Naturally, it makes sense to imagine being attacked from those same twelve directions when practising defensive moves. What matters is that the mind thinks for itself and creates sense out of the spurious myriad of kata techniques. Do not wait to be taught – it might never happen. Holding the sword vertically, somewhat similar to hasso, one can rotate it around in a horizontal axis either clockwise, or anti-clockwise. Using this, one can deflect incoming yokomen-uchi by adding firm energy to the movement at the moment of contact. The closer to the hilt the blow is received, the more leverage you have and the easier it is to deflect. However, the whole point of having a long weapon is to take advantage of the operational distance it provides. Therefore, one necessarily needs to develop the ability to deflect strong blows using a point closer to the tip – typically working one’s way up to a point about one third of the way down from the point, or two-thirds up from the hilt. Here, lacking leverage to develop power, one uses speed, timing, and courage. The opponent’s sword must be met mid-swing at full speed, and at that point of meeting, additional heavier energy must be momentarily added to strike or dash away the incoming blow. Striking it contains a greater speed element, dashing has a slightly slower speed component, but is heavier. And depending upon whether it was a clockwise or anti-clockwise rotation, the result might be either a forceful parry or an intercepting counter-strike. Similar patterns can be developed for other attacks around the clock, as noted above. Once one has a collection of distinct strikes and defences, after practising footwork and body movement in eight directions, natural avoidance and attack patterns reveal themselves. For example, moving to the rear left corner one is obviously defending one’s right side. If one’s own sword tip is down it invites attack from above, if one’s tip is up it invites attack from below. Here, one can respond by either raising, or lowering the sword respectively and making an appropriate defence and/or counter-strike. Accordingly, using the principles acquired in kata and using them while moving in each of the eight directions, one will begin to see how they all fit together. Another method to build a framework is to connect blocks and strikes together in pairs. The simplest exercise for this is to parry shomen-uchi with kaeshi-men while avoiding to the side. Next, attack shomen-uchi while one’s partner parries in the same way. If the parries are always done on the same side one will traverse in a circle. If both alternate left and right each time, one will return to the same spot every two techniques. This kind of exercise can be repeated over and over with speed and power being slowly added. With a little imagination, many more of the basic techniques can be practised in pairs like this. What’s more, their simplicity allows increased vigour, which leads to more reality. These same exercises can be done with the jo: The diversity of the jo, however, leads to even more interesting routines just waiting to be re-discovered.

(h) Realism in training Each Aikido style, and sometimes each teacher within a style, has his own method. This can not be right. The individual can not decide the method. As certain old European rennaisance texts mention, it is the nature of the weapon to the man that determines the method. Long or complicated partner forms are difficult to learn, practice, and remember. Just as any chain is only as strong as its weakest link, one's development is restricted by an inefficient method, an incomplete system, and by a slower partner who is struggling to come to terms with it. Having 'travelled' and seen what is 'out there', I no longer trust the sword I learn in the dojo, no matter where it is claimed to be from. I no longer trust that what I am shown as being a genuine sword art (if that is what is being claimed). This problem is compounded for the Aikidoka in that the sword is supposed to help better his Aikido. Thus, it has become acceptable that practice be for perfection and not for reality. And if this is to be the case, then it is absolutely vital that Aikido movement match sword movement. Yet, often it is not so. Sword offers Aikido a lot, but misunderstanding in sword feeds misunderstanding in Aikido - the purpose (for Aikidoka, not necessarily swordsmen) is for one to help the other, not hinder it. The 'Saito' weapons method that was once universal in many dojos is now losing ground to techniques, patterns, and forms from more traditional sources such as Kashima Shin Ryu, Katori Shinto Ryu, and Ono-ha Itto Ryu, etc. Indeed, many are finding remarkable similarities between the Saito method and certain traditional styles, which leads to them abandoning what they learned assuming the more traditional to be 'the original' and therefore better (not a bad argument, but not perfect either). We are presently in what appears to be a transition stage where Aikido teachers feel it important to 'return to the source', which means studying more traditional Ryu (schools) to compliment their Aikido. However, the problem with this is that people are learning a few techniques from direct sources, then teaching these 'parts' to others, who in turn pass them on, and so on. This process is perhaps inevitable, as most do not possess the half-a-lifetime necessary to study a traditional Ryu to completion. The result is a mish-mash of new ideas and techniques. The obvious problem, that is totally unrecognised and therefore perhaps not so obvious, is that there is no effort to collate all the 'new' old techniques into one complete, logical system, which is perhaps, without even knowing why, the reason that people are beginning to look elsewhere - traditional Ryu. My prediction is that this 'chaos' will continue for the forseeable future. My argument is for short forms/movements, with the intention of moving towards no-form as soon as possible. Memory of form should be replaced by perception of the moment in a rapidly changing situation. I would like to practice a system where the nature of the sword reveals itself to the serious practitioner. My personal training system: Rationale against the knife

This is not the be all and end all. My point is that, basically, a structured system means that learning builds upon learning. Think, does the style you do have a progressive system of learning? Think - Process! (i) Realism in life If you look at how people really attack with a knife, they have focused intent and make successive fast rapid stabbing motions. They often repeat the same motion, which signifies their strong intent. That intent is to puncture your body to disable or kill you. This is very different to how we train, no matter how we think it might be. The only real way to deal with such fierce intent is:

|